From the Field: Using Drones as a Landscape Performance Assessment Tool

By Rachael Shields, MLA Candidate, University of Georgia

Our University of Georgia (UGA) team is participating in the Landscape Architecture Foundation’s Case Study Investigation (CSI) program and includes professors Alfie Vick, Brian Orland, and Jon Calabria and me. We are studying Historic Fourth Ward Park in Atlanta and the University of Georgia’s Science Learning Center. The landscape architect for both projects was HDR’s Atlanta office.

Drones are currently a hot commodity in the world of package delivery or air strikes, but they are just beginning to take off in the design field (pun intended). Drones became part of our CSI research process when the need arose for high quality post-construction aerial images because online map imagery sources were not up-to-date. Collecting aerial imagery and video are increasingly common uses for drone technology in the design and planning professions. During the process of acquiring imagery, our team realized there were many fascinating advantages in using a drone — beyond the conventional uses.

The drone we used allowed us to collect data we never would have been able to otherwise. For this portion of the project, we brought in Roger Lowe, a professor in the UGA Warnell School of Forestry and Natural Resources, who is a specialist in spatial information technology and has a remote pilot certificate, also known as a “drone license.” In order to fly over UGA’s Science Learning Center, we first had to get flight clearance. Before flying, Roger made sure to check the weather and to become aware of any hazards that might affect the flight like power lines, trees, and structures. He also knew to keep the craft at a maximum of two hundred feet above ground level. While imagery with a lot of people using the landscape would be great, drone flights over people are not permitted.

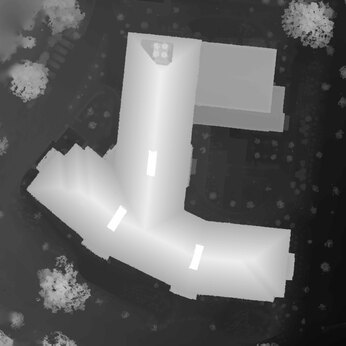

After flying, the imagery data were transferred to Agisoft PhotoScan, software that processes the images and produces data that can be opened in ArcGIS. For our research purposes, we captured a terrain file to show the topography of the site. PhotoScan also produced an orthomosaic, a seamless aerial formed from a group of orthoimages. Third, through the use of laser light reflected from terrain, structures, and vegetation, the drone is able to capture lidar data in the form of x,y,z measurements. This produces a point cloud that allows 3D analysis.

The exciting potential we began to notice with this kind of technology is longitudinal monitoring. Future classes at UGA could track changes in the Science Learning Center’s landscape over time. For example, imagery can track the change in the area of shade cover, the effectiveness of the stormwater management methods on site, or even map changes due to erosion. Additional analyses with ArcMap, Grass GIS, and HydroCAD would provide cutting-edge landscape performance evaluation tools not seen in traditional methods.

In conclusion, drones have the capacity to provide a whole new landscape performance toolset. Drone technology is new to us, and we hope to include some of the unique aspects of drone data analysis as we continue to document our projects as Landscape Performance Series Case Study Briefs. So far, we have learned that drones have great possibilities, the extent of which, we are still trying to understand.

Research Assistant Rachael Shields and Research Fellows Jon Calabria, Brian Orland, and Alfred Vick are participating in LAF’s 2018 Case Study Investigation (CSI) program, which supports academic research teams to study the environmental, social, and economic performance of exemplary landscape projects. Any opinions expressed in this article belong solely to the author. Their inclusion in this article does not reflect endorsement by LAF.