From the Field: Visual Impacts of Wind Farms

By Meaghan Keefe, 2019 LAF CSI Student Research Assistant from SUNY College of Environmental Science and Forestry

A wind farm is likely not the first image that comes to mind when you think of landscape architecture. The colossal vertical structures with their slightly futuristic but graceful blades can seem separate from, or as distinct additions to a landscape, but they are connected by more than just the energy they generate.

It is a landscape architect’s role to site wind turbines in such a way that they not only take advantage of a site’s wind patterns but also to minimize the impact to sensitive views. For the wind farms in both of our case studies, the landscape architects are responsible for the compilation of a Visual Impact Assessment (VIA) which predicts and evaluates how the turbines will affect culturally, historically, or aesthetically valuable views. Using a combination of LIDAR, GIS data, photographs, and field observations, they assess the viewsheds within the project area that will be most affected. They also use 3D models of the turbines geo-located within digital elevation models and land cover data to simulate how the proposed project will look from strategic viewpoints.

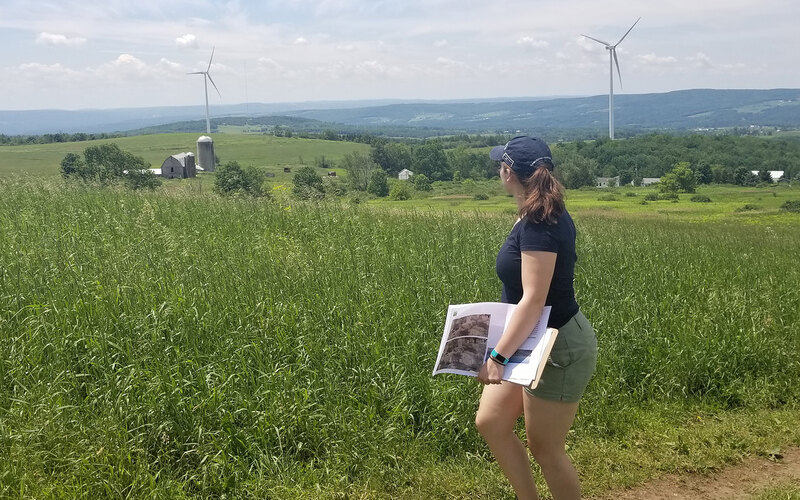

As part of the VIA, a panel of trained landscape architects rates the impact of the simulations on a scale of 1 (completely compatible) to 5 (strong visual contrast). Our research seeks to add an additional step to this process. For both of our wind farm case studies, we have returned to these sites to take the exact same photos of the completed project as were taken for the simulation before construction. In the case of the Hardscrabble Wind Farm in central New York, myself and liaisons from our partnering firm, Environmental Design & Research, retraced many of the original photos. Most of the photos proved at face value that the simulations from before the construction were very accurate. We could look at a printed copy of the simulations and with the right geographic coordinates could easily match up where the original photo was taken. Other photos we found unsuitable for direct comparison due to matured vegetation or changes in the local buildings.

For other sites, the original photo containing the simulation failed to capture multiple constructed turbines just out of shot. We noted this in our field observations, and, upon reflection with the liaison, I learned that these issues actually support newer trends and movements toward virtual and augmented reality simulations, or at the very least more panoramic simulations that would better capture a sweeping view of the landscape.

For our evaluation, we will use software such as Photoshop and ImageDiff to compare the position of the simulated and constructed turbine shafts and blades within the photographs. Each before and after image will be separated into a sky, vegetation, ground, layers and where applicable, turbine layers as well. We will then compare the percent change in color between layers, and the percent change in desaturated pixels to evaluate contrast. Determining how the turbine compares both in color and in contrast values in before and after photos may be illuminating as to the conditions that cause panel ratings of high or low contrast.

This method will allow us to understand the accuracy of simulated images as they relate to post-construction reality. It could allow for an increase in certainty for landscape architects creating VIA’s and using simulations or a tool for public engagement and educating the public about these large-scale projects. Though landscape architect panelists are trained to make these assessments, their observations are still subjective. Quantifying differences between photos could potentially reveal trends in what prompts panelists to give higher or lower contrast ratings. This, in turn, could affect how and when photos are taken, whether or not it is necessary to simulate seasonal differences, and generally highlight potential biases that could be eliminated in future VIA’s.

Renewable energy landscapes are becoming more common as we seek alternatives to fossil fuels. VIAs are important not only for physically integrating these landscapes as seamlessly as possible with existing surroundings but also for helping the public more easily accept novel introductions to a familiar landscape. Landscape architects use a myriad of technology to create simulations that aid in the communication and presentation of a project. Our case studies hope to push this even further by introducing potential new methods of quantifying the accuracy of simulations and visual contrast ratings. More accurate simulations and better understanding amongst stakeholders from the outset of a project could have a significant impact on a project’s trajectory.

CSI Team: Aidan Ackerman, ASLA, Robin E. Hoffman, PhD, Maren King, ASLA, and Meaghan Keefe, SUNY College of Environmental Science and Forestry

Project: Hardscrabble Wind Farm - Fairfield, New York

Landscape Architect: Environmental Design & Research

This CSI Participant update was written in July 2019.

Any opinions expressed in this article belong solely to the author. Their inclusion in this article does not reflect endorsement by LAF.