LAF Fellowship Spotlight: A Landscape Ethic for the San Joaquin Valley

Members of the 2020-2021 cohort of the LAF Fellowship for Innovation and Leadership have spent the past 10 months exploring big ideas and advancing their proposed projects. The Fellows will present the culmination of their work at LAF’s virtual Innovation + Leadership Symposium on June 15 and 17. In the meantime, LAF is profiling each Fellow to share more about their progress and personal journeys.

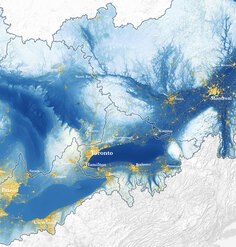

Using just 1% of US farmland, California’s Great Central Valley supplies 25% of the nation’s food, including 40% of the nation’s fruits, nuts, and other table food. This production comes at great cost to both the environment and the laborers who make this possible. Of particular significance is the southern San Joaquin Valley, which serves as a nexus for urgent challenges pertaining to global food production. Landscape architecture professor and program director Alison Hirsch has spent her fellowship year untangling the complicated set of interwoven systems that converge at the San Joaquin Valley. She aims to arrive at a landscape ethic for the working country and its connection to the global food system.

Native New Yorker Alison jokes that, eight years and two children later, she still feels like a recent transplant to California. Despite this, Fresno County (one of the eight counties that make up the San Joaquin Valley) has long lived in Alison’s cultural imagination through her Armenian grandmother’s stories, in which Fresno was a destination for past generations fleeing genocide during World War I. Curiosity drove Alison to lead a year-long capstone studio on food systems and agricultural landscapes at the San Joaquin Valley. Realizing that the full story of this remarkable region had yet to be told, Alison continued her research through the LAF Fellowship.

The human and environmental toll of food production systems in the San Joaquin Valley are myriad. As a global food production hub, the valley contends with threats posed by climate volatility, rising temperatures, exhausted water systems, contaminated soils and groundwater, and more. In turn, food insecurity, degraded air quality, high concentrations of poverty, and unmanaged urban growth are all on the rise. Racialized landscapes of labor exploitation and environmental ruin go hand-in-hand in the valley. Today its land is tilled by the most vulnerable – many of whom are undocumented migrants who often speak little or no English. These workers have limited access to information on their legal rights, and recent immigration policies have created heightened fears of deportation and loosened regulations on worker protections.

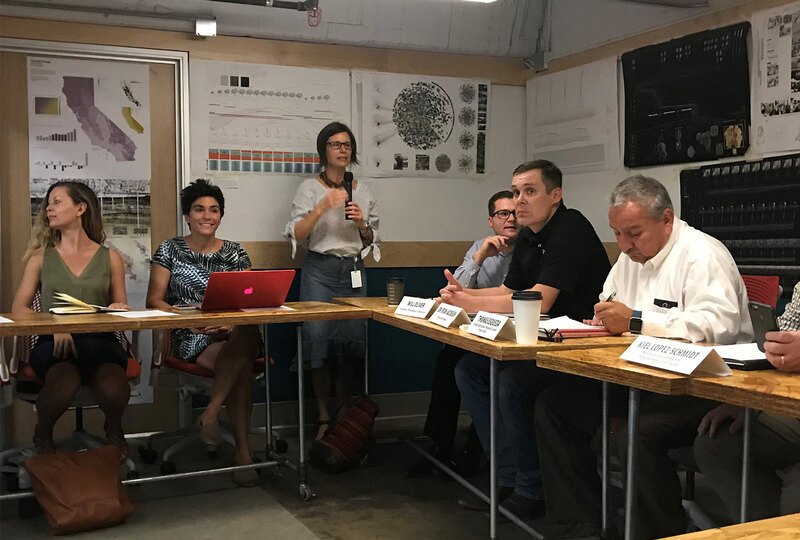

Asked about her approach to extricating the interrelated issues above to begin examining how to mitigate them, Alison shared that she is “working from the ground up – with community groups and individuals leading efforts on environmental, health, labor, and political reform at the incremental scale – and from the region down – through investigative mapping that attempts to synthesize the intersecting systems and structures that have led to the valley’s formation and dynamics today.”

Though the picture is, in many ways, grim, the cultural resilience of the workers who inhabit the land has remained a source of inspiration to Alison. In crafting a more responsible landscape ethic, she believes that prevailing narratives of resistance will be critical to establishing new paradigms moving forward. Immigrant populations have lived and worked in the region throughout its history, (quite literally) shaping the landscape and culture of the San Joaquin Valley, and Alison pushed herself to make connections in the valley that “offered the opportunity to really know a place and the challenges and fears, as well as dreams and aspirations, of those that live there.”

Reflecting on the added stress that the COVID-19 pandemic placed on the fellowship effort, Alison takes comfort in the comradery she found among the 2020-2021 cohort members. “With two young children at home from school while trying to oversee a graduate program and teach, time spent with the cohort sharing the progress of our work was particularly enriching and mutually supportive.” Roughly two months away from the LAF Symposium for Innovation and Leadership, Alison is synthesizing her methodology to emphasize process over product, as the work will continue long after the conclusion of the fellowship. “The past year has clarified for me what it means to be a socially and politically engaged scholar and how the approaches and skills of the landscape architect can be most effectively applied to make an impact across scales.”

UPDATE: You can watch Alison's presentation from the 2021 LAF Innovation + Leadership Symposium here.