LAF Fellowship Spotlight: Landscape, Incarceration, and Rehabilitation

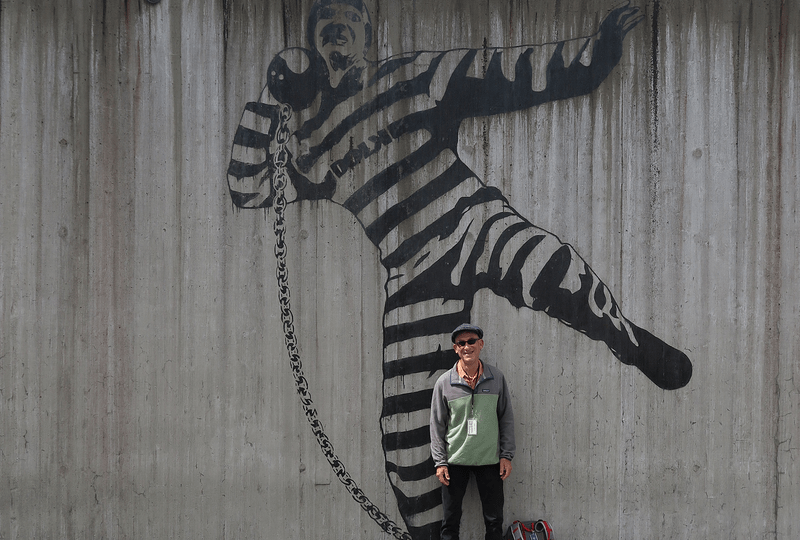

Over the past five years, the Landscape Architecture Foundation’s Fellowship for Innovation and Leadership has given more than two dozen landscape architecture professionals the opportunity to pursue important projects that tackle a variety of social issues, from climate change and environmental justice to education and emerging technologies. This fall, University of Washington landscape architecture professor Daniel Winterbottom is using his fellowship to conduct research on prisons and the role landscape plays in them. Specifically, Daniel is researching the therapeutic implications of differing carceral environmental models and how they can be positively perceived, used, and designed to facilitate or negate healing, growth, and transformation. He’s one of six Fellows in the 2022-23 cohort.

“For me, the interesting aspect is: What is the role of landscape and nature, and how can we develop more humane environments for those who need it and in many cases are denied it?” Daniel said during a recent call from Italy.

Daniel is spending the semester teaching in Italy, but also is using the trip as an opportunity to conduct research for his fellowship. The past few months have been productive, he said, with visits to prisons in the U.S., Norway, and Italy, and additional trips planned throughout Europe and the U.S. next spring. The experiences have been eye-opening for Daniel with a number of different models of nature-based therapies and assessable landscape typologies incorporated into different facilities. Those variables affect the experiences of those who are incarcerated as well as those who work at these facilities.

Daniel noted that green, therapeutic facilities are much more likely to effectively support rehabilitation and personal transformation amongst those serving time. Gardening and green therapeutic programs also reduce recidivism rates among prisoners who are ultimately released. Daniel's work comes a year after 2021-22 Fellow Olivia Bussey explored how landscape architecture can play a role in breaking the cycle of recidivism, using design to create supportive, post-incarceration networks that reduce the tendency towards reoffending.

Part of Daniel’s research includes looking at the history and evolution of incarceration, a practice that dates back millennia and was based on what Daniel calls “idealistic but flawed” concepts of isolation and work. Some of the oldest prisons were originally built within castles and churches that were later converted into places of incarceration. In the U.S., two types of prison designs were at the formative stage of carcel design: the Auburn (for example, Walnut Street Prison), focused on solitude and meditation, and the Pennsylvania model (for example, Eastern State Penitentiary), focused on work, activity and production. Few of these facilities implemented therapeutic landscape design elements. Eventually, these facilities gave way to the prisons we see today, which face unique challenges while offering specific opportunities to introduce nature into the carcel environment. Today the prototype “block” prisons compound the challenges faced by the older models, Daniel said.

Meanwhile, Europeans in the 1950’s began to think more progressively. The difference between facilities in the U.S. and those in Europe is noticeable, from the preponderance of, and access to green landscapes, to the freedom prisoners are allowed within the facilities. As an example, Daniel cited prison guards in Norway, whose role is to help prisoners in their process of reform as opposed to the traditional security roles that they play in the U.S.

“My work is really looking at international models and trying to cultivate the best of those models and to introduce them to incarceration facilities in the U.S.” Daniel said.

The topic is extremely important to Daniel, whose career has included extensive work with people dealing with trauma. Those experiences in war-torn countries like Bosnia and Herzegovina and Guatemala have helped form his social justice and empathetic perspective as he now focuses on the prison system. He has conducted numerous interviews with researchers, designers, prison officials, and even a victim of crime. He also has conducted an extensive literature review as part of his research and is working with prison officials across the U.S. and Europe to set up future visits.

Daniel has had mixed results getting access to prisons, he said, with European facilities generally being more open to his inquiries. Still, he has been pleasantly surprised by some of his interactions. And he has learned about the increase of therapeutic landscape elements in the U.S. in recent years as their benefits have been more widely publicized.

“There are many sympathetic and empathetic people within the incarceration system,” Daniel said. “It’s refreshing. The consistent problem seems to be the bureaucracy, politization, and the media treatment of incarceration.”

Despite all his progress so far, Daniel acknowledges incarceration is complex. Some who are incarcerated seem to show no remorse for their crimes and maintain little desire to rehabilitate, he said. Then there are victims and their families, and their trauma that also must be considered when thinking of therapy and equity. Still, Daniel firmly believes that the opportunity for rehabilitation is better for those incarcerated and for society in general. In Olivia's final presentation, she closed with this quote from Dr. Emma Hughes of Fresno State University: “About 95% of the people currently in prison will come back into the community one day. So something we have to ask ourselves is: what do we want to have happened to them during the time they were incarcerated”

“The well-being of inmates is really a public health issue on steroids,” Daniel said.

Daniel is thankful for the time his fellowship is allowing him to dedicate to the issue. LAF Fellows devote a total of 3 months’ time to their proposed project over the course of a year and receive $25,000 to help offset the cost of taking this time. It allows them the time and space to delve into issues most important to them and the profession.

“What LAF has given me is the time to dig deep, but also reflect and see what an activist’s role can be, looking at best designs and modalities and big policy issues, and how do we frame them to make a change on the macro level,” Daniel said.

UPDATE: You can watch Daniel's presentation from the 2023 LAF Innovation + Leadership Symposium here.