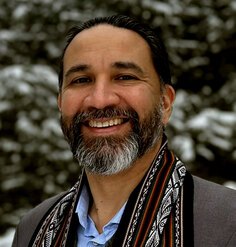

Perspectives: Fernando Magallanes

APRIL 17, 2020

Fernando Magallanes, Hon. Dr.(h.c.) PLA, ASLA is an Associate Professor of Landscape Architecture at North Carolina State University's College of Design. Throughout his career, he has collaborated with eclectic partners from around the world. His intellectual interests span just as wide a spectrum and he strongly advocates for landscape architects to incorporate disciplines beyond those typically consulted by the profession into their thinking and practice. The emergence and evolution of diverse cultures motivate Fernando to reimagine what a specific site can offer those who frequent it. As he explores and learns from various sources, he has increasingly turned to his Latino heritage as his personal anchor.

What drew you to landscape architecture?

My disinterest and dissatisfaction with organic chemistry at Texas A&M in my sophomore year led me to look for a career away from pre-veterinary medicine. My hopes of becoming a veterinarian were lost as the pre-vet science curriculum was hardly enjoyable.

I remember scrambling through the course catalog and seeing Landscape Architecture as an option. I did not know anything about this discipline but having grown up around ranchers and farmers and Saturday night family walks along the San Antonio River, the career sounded interesting. The curriculum advertised art, design, history, and something called studios. My youthful experiences enjoying the green lushness of the San Antonio River, the beauty of the Southwest landscape, the family-friendly Latino barrios (neighborhoods) of the urban city and towns I lived in, and the promise of making better landscape environments were enough to attract my commitment to this unknown profession.

I have spent over thirty years participating in the discipline. At times, I question if I made the right choice as landscape architecture rocks back and forth groping to define itself. But looking back at my career, I can confidently say landscape architecture has been rewarding. I value my exposure to many wonderful individuals in the discipline, its ongoing evolution, and the opportunities it has offered me. I have traveled and studied internationally and, most importantly, I have had the opportunity to explore my observations, lessons learned, and ideas with my students. The study of landscape architecture exposed me to many influential concepts and theories that are now part of me as I continue to teach at North Carolina State University.

What is driving you professionally right now?

I am driven by ideas and culture. In order to have more ideas, I read, I travel, I collaborate, and I explore other disciplines (illustration, graphic design, anthropology, neuroscience, sociology, psychology, history, business, art). I know how research and collaboration can enrich landscape architecture and my teaching. I have collaborated as a landscape architect with veterinarians, NC First Peoples the Tuscarora, African Americans in North Carolina neighborhoods and in Randallstown, MD, Czech Architects and Urban Designers in Prague, Bolivian Architects, Urbanists and activists in Santa Cruz, Cochabamba, and La Paz, Spanish Architects and designers in Santander and Madrid, and in Germany with business efficient German Rotary Clubs.

With each of these experiences I have become more excited by the nature of culture and how it animates and purposes the landscape people inhabit. The cultures of these geographical areas are different as they respond to geography, geomorphology, folklore, mythology, art, and cultural history. Each region visited divulged a beautifully different identity and landscape place.

This recognition of uniqueness in the landscape has driven me to renew my Mexican American values and Latino heritage. Assimilating to American values for most of my life, I sense I have strayed from my own roots. I have always been grounded by my Latino heritage and I am seeking to reinforce its expression even more. I want to teach and encourage other minorities to enter landscape architecture without losing their cultural background and to bring with them the culture of their ancestors to enrich an existing discipline that is still evolving.

What challenges are landscape architecture allowing you to address right now?

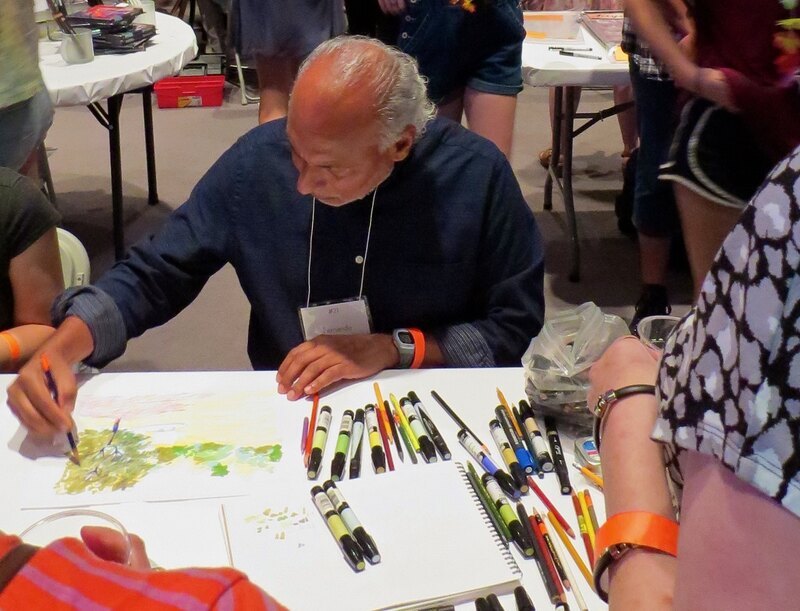

We must study how we educate landscape architects in our universities and how we practice in our firms. In recent years, research, theory, and new technology has modified our way of teaching and practicing landscape architecture. Teaching is changing as we speak but no one is leading exploration about how and what we teach. As the discipline evolves, how should you educate students? Along with education is my personal concern over the loss of emphasis on traditional drawing skills in the analysis, observation, and design exploration and application of the landscape design process. Drawing helps to cultivate cognitive knowledge of place that is important for future innovation, decision making, and imagination. Drawing skills and plein air experiences can enhance the use of technology we have available today.

There is also the challenge for landscape architecture to solve the lack of cultural diversity, representation, and leadership within our discipline’s programs, practice, and research. Our discipline must respect the DIVERSE REPRESENTATION that already exists in its membership, but also grow, mentor, and elicit an active underrepresented presence. Underrepresentation of people of color makes for a sterile accommodation and application of new landscape ideas. By this I mean, landscape architecture membership and patronage have traditionally supported a predominantly white majority in America. It is time to provide a diverse and strong ethnic base of leadership to provide design to diverse groups of people and their landscapes. Latino population is growing in size and power. This offers an opportunity to define a new landscape reflecting minorities’ values and needs for culturally specific landscape designs. If we do not know what those specific needs and values are, then let us develop them. We have to test and explore what underrepresented minorities can contribute to landscape architecture.

There is a caution in the medical field about having a minuscule amount of underrepresented minority research. The growing Latino population brings a new set of health factors to the medical profession. Dr. Esteban Burchard and Dr. Sam Oh, both biomedical professors at UCSF have discovered a medical research gap around Latinos, women, and other underrepresented minorities. They have also disclosed that medical needs are different based on genetic backgrounds. Having insufficient research on Latinos creates a medical research disparity for Latino populations and their medical problems. Burchard and Oh are forecasting that Latinos will suffer a racial and ethnic health care disparity leading to higher rates of debilitating diseases. My educated guess is landscape environments will develop the same disparity of knowledge for handling the specific environmental health needs of Latinos and other underrepresented communities.

What challenge would you give emerging leaders?

There are many challenges beyond the need for environmental reparation and maintenance of our planet. One area of interest is in recognizing that regional landscapes reflect unique historical identities of the people of that region. Leaders must be informed not by singular residents or citizens of communities but by the overall cultural and environmental continuity of a region. The differences in landscapes across the United States are due to the specific cultures, resources, land requirements, and values of its people who created the uniqueness of those areas. Knowing and recognizing customs, values, folk tales, climate, and other attributes gives us important information when mediating landscape and place.

There is an emerging challenge to work with other leaders who mediate the world environments like architects, engineers, scientists, and politicians. We need to be discussing difficult topics that surround sensitive cultural and geographic differences, especially where we propose a major change in altering places with our designs. We must establish ourselves as eminent leaders of the human side of landscape alongside the sociologist, geologist, ecologist, archaeologist, biologist and so many others who intervene in its development.

Where do you think the profession needs to go from here?

The directions are boundless and the need to collaborate has already been mentioned, but there are other areas where branching out across disciplines would be beneficial for the profession. We do not need to become neuroscientists, geneticists, or ecologists but we must know their research and engage in discussions with them about landscape and people. The University of North Carolina has a very strong neuroscience community and I often attend their lecture series. It is evident how their research gives insight into human behavior and the workings of the human brain. Their research is fascinating, but they would never consider applying it outside the lab or the design of an urban city. But, as designers, we can. Joining forces with these scientists would be a great first step to position our discipline in contributing to the global needs of environments and humans.

I suggest we reappraise our existing foundation of beliefs, create new professional collaborations, and apply knowledge in an experimental manner from many perspectives. Artistic aesthetic, historical garden values, and ecology are a few values already established within our society and accepted in our discipline, but we can continue to incorporate new concepts in building the future. When design proposals impact the lives of people, environment, culture, economics, identity, and progress, we should simultaneously be embracing ecosystems, sustainability, design, and art.

LAF's Perspectives interview series showcases landscape architects from diverse backgrounds discussing how they came to the profession and where they see it heading. Any opinions expressed in this interview belong solely to the author. Their inclusion in this article does not reflect endorsement by LAF.