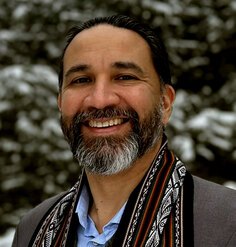

Perspectives: Michael Smith

JANUARY 7, 2022

Michael Smith is an urban designer and landscape architect at Landscape Architecture Bureau (LAB) in Washington, DC, as well as an adjunct lecturer at Howard University. His research explores systems thinking theory in urban design and adaptive ecological design in urban areas. Michael is a member of the Design Justice Work Group at the University of Pennsylvania’s Department of Landscape Architecture where he is an advocate for cultural and structural change that will support BIPOC students and faculty.

What drew you to landscape architecture?

For as long as I can remember, I have wanted to create meaningful spaces that inspire. After growing up as an art- and STEM-loving child in Washington, DC, surrounded by the majesty in the buildings and spaces around the National Mall, I began my professional career as an architect. However, I quickly developed a passion for the spaces between buildings. Through the office of a local District architect, James Cummings, I became the project manager for the annual work done on the Vietnam Veterans Memorial through the Vietnam Veterans Memorial Fund. Shortly thereafter, I found myself reading text and studying the designs of Walter Hood, Lawrence Halprin, Martha Schwartz, James Rose, James Corner, A.E. Bye, and others who were early thought-provokers. It was ultimately my interest in engaging, large-scale, environmentally-focused design thinking that led me to study landscape architecture at the University of Pennsylvania.

Now, I work to create places that can connect us emotionally and improve our quality of life. As a steward of the urban realm, I continue to investigate how I can leverage natural dynamics and constructed systems to advocate for socially and environmentally responsible design, especially through regional and local infrastructure.

What is driving you professionally right now?

I have found a great balance with design research and professional practice, particularly in extensive urban projects. I continue to develop provocations that aim to challenge the notions of space, place, and their material flows and feedback loops. My research centers on deconstructing historic infrastructure networks to evaluate, understand, and improve these dormant systems and their adjacencies. I see the built environment as a laboratory to investigate how latent historic networks intersect with the contemporary surrounding environment. My hope is to reveal, redesign, and re-enfranchise latent infrastructure networks in order to improve the quality of life in surrounding, often underserved, neighborhoods.

In addition to my research on infrastructure, I am driven to explore how innovative computational techniques can resolve problems of landscape representation, both in illustrations and in technical documentation. I’ve applied these explorations to a range of institutional, infrastructural, and civic projects while at LAB — in an ongoing 120-acre research and infrastructure project adjacent to a new highway access road with ecotones, shared-use paths, and water management infrastructure; a 420-acre green infrastructure project in the DC neighborhood of LeDroit Park; a 2-mile long renovation of DC's historic Connecticut Avenue corridor; and a 16-acre retirement community campus redevelopment located near a tributary to Rock Creek. For projects of this scope, my work interrogates antiquated analytic techniques by creating new cartographies that reveal project potentials. My goal is to tap into the agency of data and advanced computation to create a more sustainable urban landscape that is both productive and culturally engaging.

Recently I have begun several new research investigations that aim to develop urban design and landscape architecture projects that are structured by the agency of data and advanced computation. In my work, I use large datasets to create cartographies of information, then assess potential uses of this information as an agent to evaluate and build systemic urban environments. These investigations explore the interoperability of geospatial data and representation, material flow constructs, and physical and invisible infrastructure networks.

What challenges is landscape architecture allowing you to address right now?

There is a global crisis in native habitat loss. Landscape architects are uniquely positioned to address it. As a steward of spaces that serve both people and wildlife, it is my responsibility to do what I can to help address this crisis wherever possible. In my work researching and designing large urban infrastructure landscapes, I am able to take into account both people and wildlife by bridging the gap between public interest and habitat creation within urban centers. By applying adaptive ecological design as a mechanism for plant selection, my work is grounded in science and guided by aesthetics to produce landscapes that are rich in both habitat resources and transformative spatial experiences.

Through my work, I have mapped local ecological systems and identified analogous conditions in the contemporary urban environment. My built projects have allowed me to begin testing these ecological insertions in large civic landscapes in and around DC. Ultimately, I hope to develop a methodology that enables city planners, urban designers, urban foresters, and landscape architects to select urban vegetation that is grounded in a rich ecological framework at the scale of a block, street, and community. (For more details about this work, check out Shared-Uses: A Collaborative Case Study in Innovative Planting Design for Infrastructure Projects in the conference proceedings of the 2017 International Conference on Ecology and Transportation. The publication documents the methodology and design process for the development of a 120-acre, 2-mile-long road to alleviate traffic from the existing highway while increasing pollinator and avian productivity at the site.)

What challenge would you give emerging leaders?

Environmental justice is a critical spatial and environmental issue which landscape architects are uniquely suited to address through design thinking exercises and project interventions. Looming changes in legislation will create opportunities for designers and others to improve the way that we use and experience urban spaces. We have the tools to create environmentally responsible places that intertwine the art, history, culture, environmental, architectural, and sociocultural identity of the places we live. Through the design process, this shoring up of the unique qualities of space by creating meaningful places maximizes the shared values of our communities.

The Biden administration's recently passed infrastructure bill, for example, will bring a national focus on the rebuilding and renovation of transportation infrastructures. Many of these infrastructure systems are directly adjacent to or bisect underrepresented communities. When the federal and local Departments of Transportation fund these projects, how can these public utilities be repositioned to better serve and connect marginalized areas?

Along with questions of injustice, of course, the impacts of climate change must be addressed. In the rebuilding of our country's infrastructure lines, how do we create better landscape areas within these public easements that promote local habitat productivity and fight climate change?

I challenge emerging leaders to actively engage in these conversations and be advocates for innovation. Join the conversation in whatever capacity you can to help guide the narrative toward meaningful and systemic change. Speak out through community engagement, design provocations, scholarly works, professional projects, attending public events, supporting those who work in this sector through donations, and any other means that furthers the conversations and provides solutions to these social and environmental injustices.

Where do you think the profession needs to go from here?

In recent years, a wealth of new research and data has emerged in the sciences about what makes nature function in and around the built environment. Yet most designers of urban landscapes continue to use antiquated practices and outdated science at the core of their design process. The profession as a whole needs to adopt, integrate, and implement the use of newer tools, data, and research to advance the industry to be able to adapt and take action to address the urgent issues during these uncertain times.

LAF's Perspectives interview series showcases landscape architects from diverse backgrounds discussing how they came to the profession and where they see it heading. Any opinions expressed belong solely to the interviewee. Their inclusion in this article does not reflect endorsement by LAF.