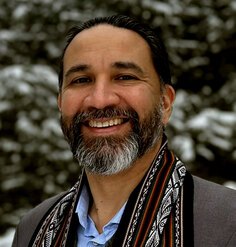

Perspectives: Catherine De Almeida

MARCH 25, 2022

Catherine De Almeida is an Assistant Professor of Landscape Architecture at the University of Washington. Trained as a landscape architect and building architect, her research examines the materiality and performance of waste landscapes through exploratory methods. Her "landscape lifecycles" work has been supported by numerous grants and recognized in national and international publications and media outlets.

What drew you to landscape architecture?

While I was an undergraduate architecture student at Pratt , I took a couple of courses — Ecology for Architects and an Introduction to Landscape Architecture course taught by Signe Nielson — which compelled me to apply to MLA programs. These courses were a breath of fresh air for me in terms of offering insights and tools for thinking more broadly and holistically.

Once I got into landscape architecture, there was no turning back. The ability to think both short-term and long-term, designing with change over time and across multiple scales, helped broaden my definitions and understanding of design. To study landscape is to consider multiple histories, time scales, and communities simultaneously. It is a medium to illuminate how interconnected we all are through time and space, and the amplifying effects that human decisions have on different living beings.

What is driving you professionally right now?

I am passionate about recognizing and honoring the objects, spaces, and communities that have been and continue to be marginalized based on how they are perceived and treated by dominant culture. As a queer, first-generation, Portuguese American, my identity is often perceived as ambiguous or vague, causing me to occupy many different spaces while often feeling racial and ethnic imposter syndrome in all of them. This ambiguity has granted me both advantages and disadvantages in American society. Having experienced the ways in which I am treated differently depending on how others interpret my identity based on my appearance, I have approached the idea of “waste” as a category of objects, spaces, and communities that are assigned value or worthlessness by the shifting biases of the dominant culture.

Waste has an ambiguous identity, as its meanings are dictated by cultural values. I define “waste” generally as that which is left over from socio-economic, urban, and industrial processes. This ambiguity offers many kinds of interpretations and possibilities to break the assumption that what is known today is not the way things always have been and will continue to be; there is no absolute or only one way to categorize, see, or do things. Queer spatial theory emphasizes ideas of multiplicity and heterogeneity, or ambiguity. I approach my work through this lens of pluralism and intersectionality and am interested in how things and spaces can be more than they appear to be, and can take on multiple identities and uses, determined by different users and communities.

What challenges is landscape architecture allowing you to address right now?

Exploitative resource consumption and unrestricted waste production are causing water, food, climate, and ecological crises. Waste is currently one of our most abundant renewable resources. While there is a vast array of different types of waste, they are managed and treated similarly. The core questions I ask to address this challenge are: How might waste become a source of renewal? Can waste and systems of recovery receive more investment than systems of extraction? And if so, how might this reshape built environments?

To grapple with these questions, I have been developing a term “landscape lifecycles” as a design research approach in which I apply a materials lifecycle lens to the inventory, analysis, and design of waste landscapes as integrative and holistic systems. I use this framework to investigate the performance, visibility, citizenships, emotions, and injustices of waste materials and landscapes. Landscape architecture allows me to broaden typical definitions of inputs and outputs in lifecycle assessments to include the human, more-than-human, perceptual, and spatial dimensions of waste.

Design and landscape architecture are creative spaces to explore alternate realities. Through this lens of ambiguity, I continually search for opportunities to combine and integrate things perceived as disconnected into newly woven wholes. The larger goal of my work is addressing issues of equity and justice by changing cultural attitudes toward waste in order to change how it is engaged with and managed. Because waste is ambiguous, some of its various identities have yet to be defined as an integral aspect of society. Waste can be the antidote to waste.

What challenge would you give emerging leaders?

The primary challenge I give to emerging leaders is to not default to repeating how things are or have been, but to explore what they are not or have not been and embrace their unique qualities. Just because it does not exist, does not mean it can’t. This is the power of design: to imagine new realities beyond what exists today and explore creative acts of reuse. I challenge emerging leaders to embrace ambiguity and celebrate the things that do not fit in a specific box, definition, or expectation.

Where do you think the profession needs to go from here?

The profession needs to approach design through a lens of multiplicity, heterogeneity, and continual renewal. Find the connections between things that are considered separate. Understand the larger-scale ramifications of design decisions — from where materials are sourced to where they are disposed — and who is impacted by these decisions.

Design does not stop at the site, nor does it end after construction; it can shift to include longer project time spans that prioritize waste transformation in all stages and lives of a project. To embody a design ethos of waste transformation requires building in mechanisms within a design to reuse waste throughout the life of a project, or at least provide avenues for reuse and transformation to occur. Waste can be a source for novel relationships.

In an upcoming chapter in The Routledge Handbook of Contemporary Themes in Urban Landscape Architecture Research titled “Landscape Lifecycles: Renewed Principles for Waste in Urban Landscape Design,” I offer a series of principles for waste in design. These are grounded in the interrelationship between attitudes and behaviors. Behaviors cannot be changed without changing attitudes.

The profession can change these attitudes through design, and I propose the following as design guidelines for where we go from here (further detailed in the chapter): Waste is life, not death; Infinite uses, not infinite resources; Multiple, not single; Flexible, not rigid; and Human economies of care, not monetary economies of extraction.

LAF's Perspectives interview series showcases landscape architects from diverse backgrounds discussing how they came to the profession and where they see it heading. Any opinions expressed in this interview belong solely to the author. Their inclusion in this article does not reflect endorsement by LAF.