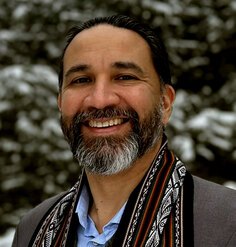

Perspectives: Sami Sikanas

April 27, 2023

Sami Sikanas is a landscape architectural designer at Marvel in New York City. Over her 8 years of experience working in NYC, she has designed and managed various landscape projects in and around the city, including parks, plazas, and waterfronts. She is also the curator of the Queer Landscapes platform, where she interrogates identity and its manifold relationships to design.

What drew you to landscape architecture?

At a young age, I had a strong relationship with nature and the environment. I think back to my childhood home in rural Michigan, and how vivid I can imagine the landscape around it: the lake where I would swim, the swamp where I’d explore, and the sand pit in the lot across the street where I’d play. Even though I had grander ambitions that would take me out of that small town, I am thankful for my time there. I think that my close connection to nature, combined with the appreciation of beauty and art imbued in me by my mother, an art teacher at the time, eventually brought me to the profession. Landscape architecture, for me, is the perfect combination of science and art. I can be a nerd and be creative at the same time — the dream!

What is driving you professionally right now?

We do not work in a vacuum, and in every project, I’m driven by societal and environmental needs: what does the community want, what does it need? How can we at least improve the existing natural systems and alleviate the pressure people place on the environment? Projects vary in their relationship to the public and nature — some are private and urban — but I think there is always an opportunity to address social and environmental justice issues, even if indirectly.

I’m also at the stage in my career when I can finally see my projects come to life. They are being built and used by people, which is incredibly exciting. It’s an opportunity for me to see what works and what doesn’t, which is preparing me as I advance further in my career.

What challenge is landscape architecture allowing you to address right now?

I’m excited by the attention to social justice and equity in the profession right now, both in our projects and in our workplaces. I’m working internally on Marvel’s DEI initiatives with my amazing colleagues, and I advocate for queer and trans representation in the profession through my participation with Build Out Alliance and ASLA’s Gender Equity Task Force. I’m aware that, not long ago, a trans person working professionally in landscape architecture was nearly impossible. Progress has been made, but still more needs to be done. I worry about the future generations of trans people. We try to address diversity and representation in the profession by thinking about the pipeline into it — are the people we need at the table not even in the room? If trans people are limited in their trajectory as they grow up, by legislation for example, our seat at the table isn’t guaranteed. Through my work, I can make trans people visible, which is part of what needs to be done to ensure our existence in the future.

Landscape architecture allows me to address social justice through the projects I’m working on as well. I’m currently working on three affordable housing developments in the Bronx and their public spaces. New York City has a major housing crisis, as I’m sure many readers are aware. If architects’ goals are achieved through the building of affordable housing itself, my goal as a landscape architect is to make their experience as enjoyable, beautiful, and connected to nature as possible.

What challenge would you give emerging leaders?

I’d challenge my generation of emerging leaders to rethink our relationship to work. The COVID-19 pandemic has had implications that we’re still grappling with. We’ve transitioned to hybrid work—what is next? Too many people leave the profession because they experience burn-out, and it usually happens right around the phase of their career that I’m currently in. It is a constant goal of mine to maintain a healthy relationship with work, so I can stay in the field of landscape architecture, and do what I love, as long as possible. Hybrid work has helped dramatically to maintain my mental health and I haven’t quite experienced burn-out yet. Next, I want us to think collectively about the value of our work — can we operate, win projects, continue to grow, etc. while providing more time off, paid overtime, better benefits, higher pay, and maybe even a 4-day workweek?

Where do you think the profession needs to go from here?

In addition to rethinking our relationship with work and continuing to address social and environmental justice internally and through our projects, I think we need to promote our profession to the country and the world. The fact that I didn’t know the profession of landscape architecture existed when I was growing up, even with my strong connection to nature and art, but I knew what architecture was, is a failure on our part. Landscape architecture is embedded into our daily lives: by the streets that we walk on, the parks we play in, the campuses we learn in, and the plazas we protest in. Our work is the practical application of art and science and can change the world. In our climate-changing, diversifying future, our role is more crucial than ever, and we need to make sure that politicians and the public are aware of our value.

LAF's Perspectives interview series showcases landscape architects from diverse backgrounds discussing how they came to the profession and where they see it heading. Any opinions expressed in this interview belong solely to the author. Their inclusion in this article does not reflect endorsement by LAF.