LAF Fellow Aaron Hernandez is Illuminating How Policy Shapes the Land in Toronto

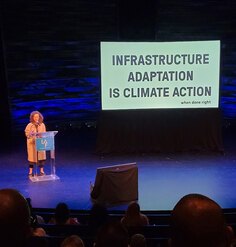

In summer of 2024, the Toronto area had one of its largest floods on record. This came only 11 years after another of the largest floods the city had ever seen. Modern water infrastructure has been unable to keep up with the unprecedented flooding. “Toronto’s relationship with water is broken, and it’s broken because the city, the province of Ontario, and Canada itself have evolved under government by industry,” asserted LAF Fellow Aaron Hernandez during his presentation at the 2025 LAF Innovation + Leadership Symposium.

Aaron sees these floods as not only a concerning sign of climate change, but an opportunity to rethink our relationship with land and water in the city. With the help of his Toronto Policy Atlas and a legal framework based on principles of Indigenous and First Nation populations, Aaron hopes to change the way we view, legislate, and interact with the world around us.

While pursuing an English degree, Aaron’s passion for the environment was sparked when he came across “Living by Life: Some Bioregional Theory and Practice”, an essay by Jim Dodge. The essay introduced him to the concept of bioregionalism and brought forth questions for him such as, “How do we govern ourselves in relation to nature?” and “What does a bioregion look like?” In consideration of these and other similar questions, Aaron felt inspired to apply his skills in communications toward environmental justice. He chose to pursue a Master of Landscape Architecture from the University of Toronto to build and sharpen the skills he would need to be able to technically diagnose and address the issues he was so passionate about. Aaron went on to gain hands-on experience at Reed Hilderbrand, a landscape architecture firm in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

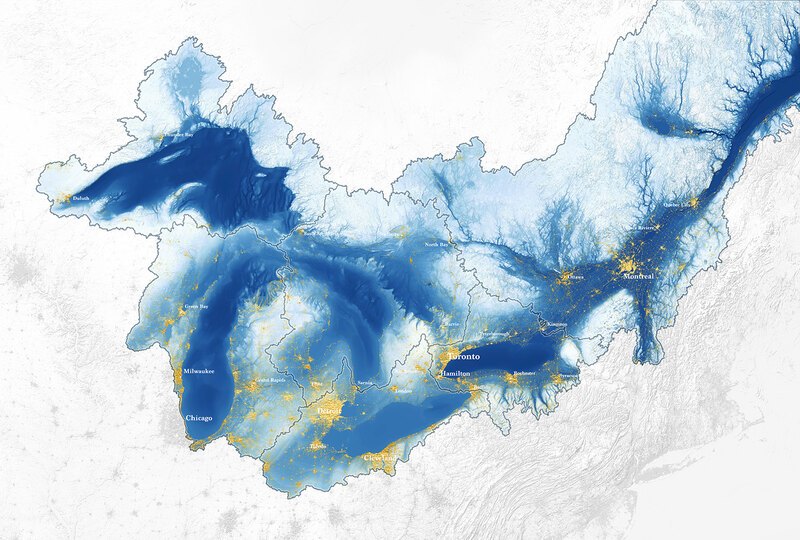

Through the Toronto Policy Atlas, which he began during his 2024-25 LAF Fellowship, Aaron uses mapping and design tools to explore the effects of public policy on shaping the land and the consequences that have become apparent through increased flooding and water pollution, emphasizing that efforts to control water with rigid infrastructure will inevitably fail if they ignore the land’s natural composition. “Instead of grappling with the root of the problem — that zoning and property rights have broken our relationship to land — Toronto’s policy response has been to treat the symptoms,” Hernandez notes. “Of the $7 billion Toronto is investing in stormwater management, three quarters is directed towards trying to control water with bigger and bigger pipes.”

With the help of his Toronto Policy Atlas and the input of his cohort of LAF Fellows, Aaron inferred that land’s profitability through the resources it offers, or lack thereof, is what determines whether it can be considered for preservation. This is one of many phenomena that the Atlas can help illustrate to both the general public and lawmakers alike. “Policies are often just written documents that rarely have clear spatial relationships,” Aaron explained. “That lack of a spatial program is why a lot of environmental policy is ineffectual or not enacted.”

Aaron’s goal is that this project inspires people to see connections between the abstractions of public policy and the landscapes they inhabit, and to think about new ways in which policy can recognize the agency of land and water, starting in the Toronto area. “The Atlas is meant to be a public resource to understand the past a little bit better and understand how the past has shaped the present,” he reflected in a recent interview. Where the Atlas provides viewable facts to make a case for environmental conservation measures, practices centered around environmental personhood provide a legal framework to fall back on.

Environmental personhood is the concept of bestowing the legal and judicial rights of a person on specific environmental entities. This allows them to be represented in court to enforce certain protections against pollution, exploitation, and destruction. Some credit a 1970s article by Professor Christopher D. Stone with introducing this idea. In reality, Indigenous and First Nation peoples had long engaged in similar practices, managing the land based on principles of respect and reciprocity rather than profit-driven models of exploitation.

Aaron says, “Ultimately I hope the Atlas helps people see the world differently, as a first step in thinking about the world differently. The idea that a river is alive might be a radical concept to some people, but the more we understand that rivers function like other living beings, and the more we understand about legal concepts like ‘personhood’, the more equipped we are as a society to make the kinds of transformational change necessary for responding to the climate and biodiversity crises.” Aaron believes Rouge National Urban Park would be an excellent case to begin thinking about the application of environmental personhood in the Toronto area.

Aaron credits the LAF Fellowship for providing his project with the structure it needed to reach its fullest potential. The supportive environment armed him with the constructive criticism necessary to shape and sharpen his project and enable him to utilize the June 5 symposium as a platform to expand his impact. “It’s different from writing a paper in a journal and sending it out and having 12 people read it,” Hernandez said of his time in the fellowship. “To be able to speak to practitioners and people who are in allied disciplines is an amazing opportunity, so I’m super grateful to have been able to go through that over the past year.”

For those interested in learning more about efforts to increase environmental personhood and whether any initiatives are under way in their area, Aaron recommends perusing resources such as the Eco Jurisprudence Monitor at ecojurisprudence.org.

You can watch Aaron's presentation from the 2025 LAF Innovation + Leadership Symposium here.